Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello & Harpsichord - Allegro

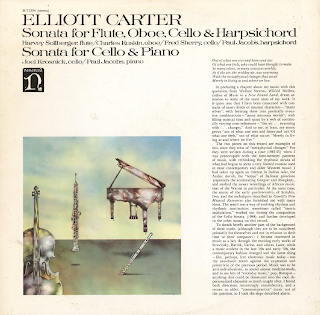

Elliott Carter

Sonata for Flute, Obeo, Cello & Harpsichord

Harvey Sollberger: Flute

Charles Kusin: Oboe

Fred Sheery: Cello

Paul Jacobs: Harpsichord

Sonata For Cello & Piano

Joel Krosnick: Cello

Paul Jacobs: Piano

Coordinator: Teresa Stone

Art Director: William S. Harvey

Cover Art: Peter Schaumann

Cover Design: Robert L. Heimall

Cover Concept: Hess and/or Antupit

Recorded under the musical supervision of the composer

Recording Engineer: Marc J. Aubort

Nonsuch Records H-71234

1969

From the back cover: When I was asked in 1947 to write a work for the American Cellist Bernard Greenhouse, I immediately began to consider the relation of the cello and piano, and came to the conclusion that since there were such great differences in expression and sound between them, there was no point in concealing tase as had usually been done in works of the sort. Rather it could be meaningful to make these very differences one of the points of the piece. So the opening Moderato presents the cello in its warm expressive character, playing a long melody in rather free style, which the piano percussively marks a regular clock-like ticking. This is interrupted in various ways, probably (I think) to situate it in a musical context that indicates that the extreme disassociation between the two is neither a matter of random or indifference but to be heard as having an intense, almost fateful character.

The Vivace, a breezy treatment of a type of pop music, verges on a parody of some Americanizing colleagues of the time. Actually it make explicit the undercurrent of jazz technique suggested in the previous movement by the freely performed melody against a strict rhythm. The following Adagio is a long, expanding, recitative-like melody for the cello, all its phrases interrelated by metric modulations. The finale, Allegro, like the second movement based on pop rhythms, is a free rondo with numerous changes of speed that ends up by returning to the beginning of the first movement with the roles of the cello and piano reversed.

As I have said, the idea of metrical modulation came to me while writing this piece, and its use becomes more elaborated from the second movement on. The first movement, written last after the concept had been quite thoroughly explored, presents one of the pieces basic ideas: the contrast between psychological time (in the cello) and chronometric time (in the piano), their combination producing musical or "virtual" time. The whole is one large motion in which all the parts are interrelated in speed and often in idea; even the breaks between movements are slurred over. That is: at the end of the second movement, the piano predicts the notes and speed of the cello's opening of the third, while the cello's conclusion of the third predicts in a similar way the piano's opening of the fourth, and this movement concludes with a return to the beginning in a circular way like Joyce's Finnegan's Wake.

The Sonata for Flute, Obeo, Cello and Harpsichord was commissioned by the Harpsichord Quartet of New York and uses the instruments of which that ensemble was composed. My idea was to stress as much as possible the vast and wonderful array of tone-colors available on the modern harpsichord (the large Pleyel, for which this was first written, produces 36 different colors, many of which can be played in pairs, one for each hand; the Dowd that Paul Jacobs uses for this recording even has "half-hitches" which permits the different colors to be played at half as well as full force). The three other instruments are treated for the most part as a frame for the harpsichord. This aim of using the wide variety of the harpsichord involved many tone-colors which can only be produced very softly and therefore conditioned very drastically the type and range of musical expression, all the details of shape, phrasing, rhythm, texture, as well as the large form. At the time (in 1952, before the harpsichord had made its way into pop) it seemed very important to have the harpsichord speak in a new voice, expressing characters unfamiliar to its extensive Baroque repertory.

The music starts, Risoluot, with a splashing dramatic gesture whose subsiding ripples form the rest of the movement. The Lento is an expressive dialogue between the harpsichord and the others with an undercurrent of fast music that bursts out briefly near the end. The Allegro, with its gondolier's dance fading into other dance movements, is cross-cut like a movie – at times it superimposes one dance on another. – Elliot Carter

Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello & Harpsichord (1952)

1. Risoluto

2. Lento

3. Allegro

Sonata for Cello & Piano (1948)

1. Moderator

2. Vivace, Molto Leggiero

3. Adagio

4. Allegro

No comments:

Post a Comment

Howdy! Thanks for leaving your thoughts!